committed by

GitHub

GitHub

199 changed files with 11796 additions and 1110 deletions

@ -2,7 +2,7 @@ name: Issue Manager |

|||

|

|||

on: |

|||

schedule: |

|||

- cron: "10 3 * * *" |

|||

- cron: "13 22 * * *" |

|||

issue_comment: |

|||

types: |

|||

- created |

|||

@ -16,6 +16,7 @@ on: |

|||

|

|||

permissions: |

|||

issues: write |

|||

pull-requests: write |

|||

|

|||

jobs: |

|||

issue-manager: |

|||

@ -26,7 +27,7 @@ jobs: |

|||

env: |

|||

GITHUB_CONTEXT: ${{ toJson(github) }} |

|||

run: echo "$GITHUB_CONTEXT" |

|||

- uses: tiangolo/[email protected].0 |

|||

- uses: tiangolo/[email protected].1 |

|||

with: |

|||

token: ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }} |

|||

config: > |

|||

@ -35,8 +36,8 @@ jobs: |

|||

"delay": 864000, |

|||

"message": "Assuming the original need was handled, this will be automatically closed now. But feel free to add more comments or create new issues or PRs." |

|||

}, |

|||

"changes-requested": { |

|||

"waiting": { |

|||

"delay": 2628000, |

|||

"message": "As this PR had requested changes to be applied but has been inactive for a while, it's now going to be closed. But if there's anyone interested, feel free to create a new PR." |

|||

"message": "As this PR has been waiting for the original user for a while but seems to be inactive, it's now going to be closed. But if there's anyone interested, feel free to create a new PR." |

|||

} |

|||

} |

|||

|

|||

@ -34,8 +34,7 @@ jobs: |

|||

if: ${{ github.event_name == 'workflow_dispatch' && github.event.inputs.debug_enabled == 'true' }} |

|||

with: |

|||

limit-access-to-actor: true |

|||

- uses: docker://tiangolo/latest-changes:0.3.0 |

|||

# - uses: tiangolo/latest-changes@main |

|||

- uses: tiangolo/[email protected] |

|||

with: |

|||

token: ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }} |

|||

latest_changes_file: docs/en/docs/release-notes.md |

|||

|

|||

@ -0,0 +1,298 @@ |

|||

# Environment Variables |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

If you already know what "environment variables" are and how to use them, feel free to skip this. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

An environment variable (also known as "**env var**") is a variable that lives **outside** of the Python code, in the **operating system**, and could be read by your Python code (or by other programs as well). |

|||

|

|||

Environment variables could be useful for handling application **settings**, as part of the **installation** of Python, etc. |

|||

|

|||

## Create and Use Env Vars |

|||

|

|||

You can **create** and use environment variables in the **shell (terminal)**, without needing Python: |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Linux, macOS, Windows Bash |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

// You could create an env var MY_NAME with |

|||

$ export MY_NAME="Wade Wilson" |

|||

|

|||

// Then you could use it with other programs, like |

|||

$ echo "Hello $MY_NAME" |

|||

|

|||

Hello Wade Wilson |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Windows PowerShell |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

// Create an env var MY_NAME |

|||

$ $Env:MY_NAME = "Wade Wilson" |

|||

|

|||

// Use it with other programs, like |

|||

$ echo "Hello $Env:MY_NAME" |

|||

|

|||

Hello Wade Wilson |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

## Read env vars in Python |

|||

|

|||

You could also create environment variables **outside** of Python, in the terminal (or with any other method), and then **read them in Python**. |

|||

|

|||

For example you could have a file `main.py` with: |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="3" |

|||

import os |

|||

|

|||

name = os.getenv("MY_NAME", "World") |

|||

print(f"Hello {name} from Python") |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

The second argument to <a href="https://docs.python.org/3.8/library/os.html#os.getenv" class="external-link" target="_blank">`os.getenv()`</a> is the default value to return. |

|||

|

|||

If not provided, it's `None` by default, here we provide `"World"` as the default value to use. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

Then you could call that Python program: |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Linux, macOS, Windows Bash |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

// Here we don't set the env var yet |

|||

$ python main.py |

|||

|

|||

// As we didn't set the env var, we get the default value |

|||

|

|||

Hello World from Python |

|||

|

|||

// But if we create an environment variable first |

|||

$ export MY_NAME="Wade Wilson" |

|||

|

|||

// And then call the program again |

|||

$ python main.py |

|||

|

|||

// Now it can read the environment variable |

|||

|

|||

Hello Wade Wilson from Python |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Windows PowerShell |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

// Here we don't set the env var yet |

|||

$ python main.py |

|||

|

|||

// As we didn't set the env var, we get the default value |

|||

|

|||

Hello World from Python |

|||

|

|||

// But if we create an environment variable first |

|||

$ $Env:MY_NAME = "Wade Wilson" |

|||

|

|||

// And then call the program again |

|||

$ python main.py |

|||

|

|||

// Now it can read the environment variable |

|||

|

|||

Hello Wade Wilson from Python |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

As environment variables can be set outside of the code, but can be read by the code, and don't have to be stored (committed to `git`) with the rest of the files, it's common to use them for configurations or **settings**. |

|||

|

|||

You can also create an environment variable only for a **specific program invocation**, that is only available to that program, and only for its duration. |

|||

|

|||

To do that, create it right before the program itself, on the same line: |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

// Create an env var MY_NAME in line for this program call |

|||

$ MY_NAME="Wade Wilson" python main.py |

|||

|

|||

// Now it can read the environment variable |

|||

|

|||

Hello Wade Wilson from Python |

|||

|

|||

// The env var no longer exists afterwards |

|||

$ python main.py |

|||

|

|||

Hello World from Python |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

You can read more about it at <a href="https://12factor.net/config" class="external-link" target="_blank">The Twelve-Factor App: Config</a>. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

## Types and Validation |

|||

|

|||

These environment variables can only handle **text strings**, as they are external to Python and have to be compatible with other programs and the rest of the system (and even with different operating systems, as Linux, Windows, macOS). |

|||

|

|||

That means that **any value** read in Python from an environment variable **will be a `str`**, and any conversion to a different type or any validation has to be done in code. |

|||

|

|||

You will learn more about using environment variables for handling **application settings** in the [Advanced User Guide - Settings and Environment Variables](./advanced/settings.md){.internal-link target=_blank}. |

|||

|

|||

## `PATH` Environment Variable |

|||

|

|||

There is a **special** environment variable called **`PATH`** that is used by the operating systems (Linux, macOS, Windows) to find programs to run. |

|||

|

|||

The value of the variable `PATH` is a long string that is made of directories separated by a colon `:` on Linux and macOS, and by a semicolon `;` on Windows. |

|||

|

|||

For example, the `PATH` environment variable could look like this: |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Linux, macOS |

|||

|

|||

```plaintext |

|||

/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/sbin |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

This means that the system should look for programs in the directories: |

|||

|

|||

* `/usr/local/bin` |

|||

* `/usr/bin` |

|||

* `/bin` |

|||

* `/usr/sbin` |

|||

* `/sbin` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Windows |

|||

|

|||

```plaintext |

|||

C:\Program Files\Python312\Scripts;C:\Program Files\Python312;C:\Windows\System32 |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

This means that the system should look for programs in the directories: |

|||

|

|||

* `C:\Program Files\Python312\Scripts` |

|||

* `C:\Program Files\Python312` |

|||

* `C:\Windows\System32` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

When you type a **command** in the terminal, the operating system **looks for** the program in **each of those directories** listed in the `PATH` environment variable. |

|||

|

|||

For example, when you type `python` in the terminal, the operating system looks for a program called `python` in the **first directory** in that list. |

|||

|

|||

If it finds it, then it will **use it**. Otherwise it keeps looking in the **other directories**. |

|||

|

|||

### Installing Python and Updating the `PATH` |

|||

|

|||

When you install Python, you might be asked if you want to update the `PATH` environment variable. |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Linux, macOS |

|||

|

|||

Let's say you install Python and it ends up in a directory `/opt/custompython/bin`. |

|||

|

|||

If you say yes to update the `PATH` environment variable, then the installer will add `/opt/custompython/bin` to the `PATH` environment variable. |

|||

|

|||

It could look like this: |

|||

|

|||

```plaintext |

|||

/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/sbin:/opt/custompython/bin |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

This way, when you type `python` in the terminal, the system will find the Python program in `/opt/custompython/bin` (the last directory) and use that one. |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Windows |

|||

|

|||

Let's say you install Python and it ends up in a directory `C:\opt\custompython\bin`. |

|||

|

|||

If you say yes to update the `PATH` environment variable, then the installer will add `C:\opt\custompython\bin` to the `PATH` environment variable. |

|||

|

|||

```plaintext |

|||

C:\Program Files\Python312\Scripts;C:\Program Files\Python312;C:\Windows\System32;C:\opt\custompython\bin |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

This way, when you type `python` in the terminal, the system will find the Python program in `C:\opt\custompython\bin` (the last directory) and use that one. |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

So, if you type: |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ python |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Linux, macOS |

|||

|

|||

The system will **find** the `python` program in `/opt/custompython/bin` and run it. |

|||

|

|||

It would be roughly equivalent to typing: |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ /opt/custompython/bin/python |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Windows |

|||

|

|||

The system will **find** the `python` program in `C:\opt\custompython\bin\python` and run it. |

|||

|

|||

It would be roughly equivalent to typing: |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ C:\opt\custompython\bin\python |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

This information will be useful when learning about [Virtual Environments](virtual-environments.md){.internal-link target=_blank}. |

|||

|

|||

## Conclusion |

|||

|

|||

With this you should have a basic understanding of what **environment variables** are and how to use them in Python. |

|||

|

|||

You can also read more about them in the <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Environment_variable" class="external-link" target="_blank">Wikipedia for Environment Variable</a>. |

|||

|

|||

In many cases it's not very obvious how environment variables would be useful and applicable right away. But they keep showing up in many different scenarios when you are developing, so it's good to know about them. |

|||

|

|||

For example, you will need this information in the next section, about [Virtual Environments](virtual-environments.md). |

|||

|

After Width: | Height: | Size: 44 KiB |

|

After Width: | Height: | Size: 61 KiB |

|

After Width: | Height: | Size: 44 KiB |

|

After Width: | Height: | Size: 43 KiB |

@ -0,0 +1,154 @@ |

|||

# Cookie Parameter Models |

|||

|

|||

If you have a group of **cookies** that are related, you can create a **Pydantic model** to declare them. 🍪 |

|||

|

|||

This would allow you to **re-use the model** in **multiple places** and also to declare validations and metadata for all the parameters at once. 😎 |

|||

|

|||

/// note |

|||

|

|||

This is supported since FastAPI version `0.115.0`. 🤓 |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

This same technique applies to `Query`, `Cookie`, and `Header`. 😎 |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

## Cookies with a Pydantic Model |

|||

|

|||

Declare the **cookie** parameters that you need in a **Pydantic model**, and then declare the parameter as `Cookie`: |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.10+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="9-12 16" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/cookie_param_models/tutorial001_an_py310.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.9+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="9-12 16" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/cookie_param_models/tutorial001_an_py39.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.8+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="10-13 17" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/cookie_param_models/tutorial001_an.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.10+ non-Annotated |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Prefer to use the `Annotated` version if possible. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="7-10 14" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/cookie_param_models/tutorial001_py310.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.8+ non-Annotated |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Prefer to use the `Annotated` version if possible. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="9-12 16" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/cookie_param_models/tutorial001.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

**FastAPI** will **extract** the data for **each field** from the **cookies** received in the request and give you the Pydantic model you defined. |

|||

|

|||

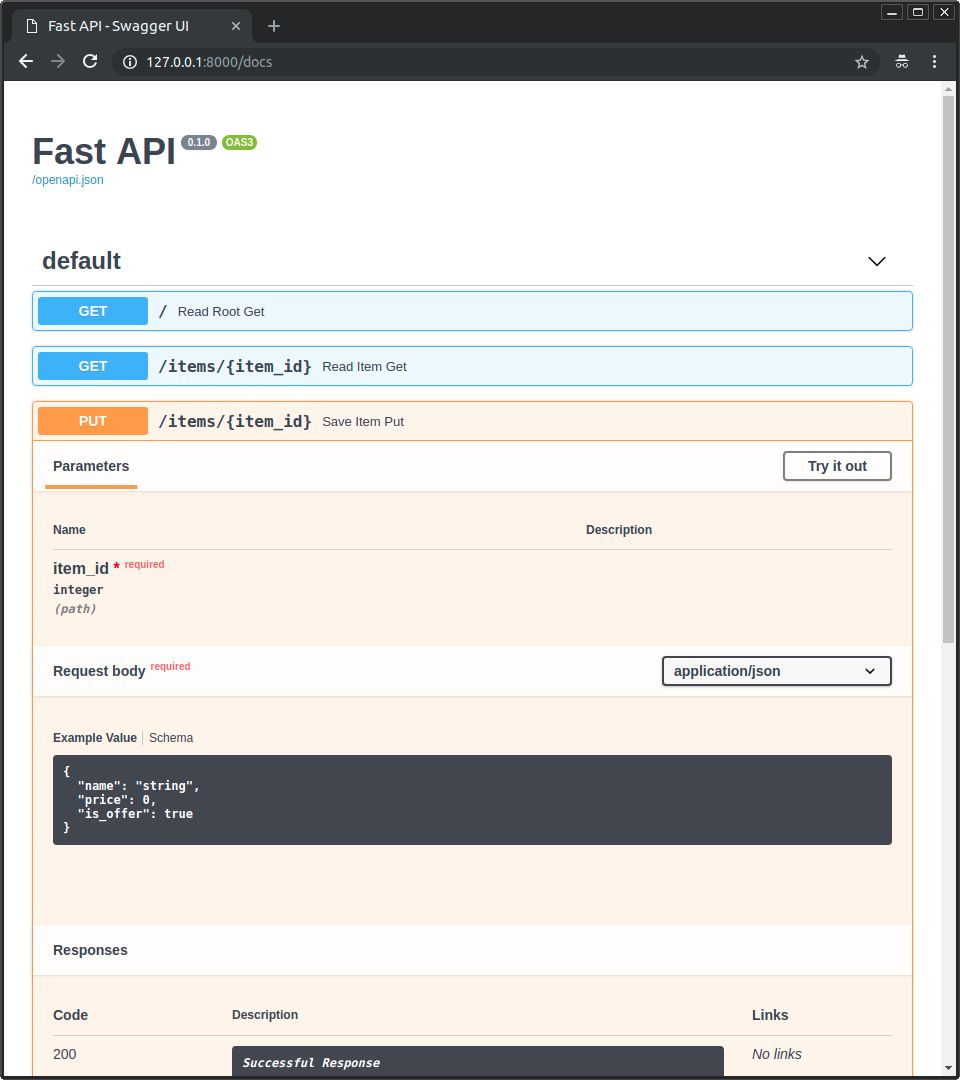

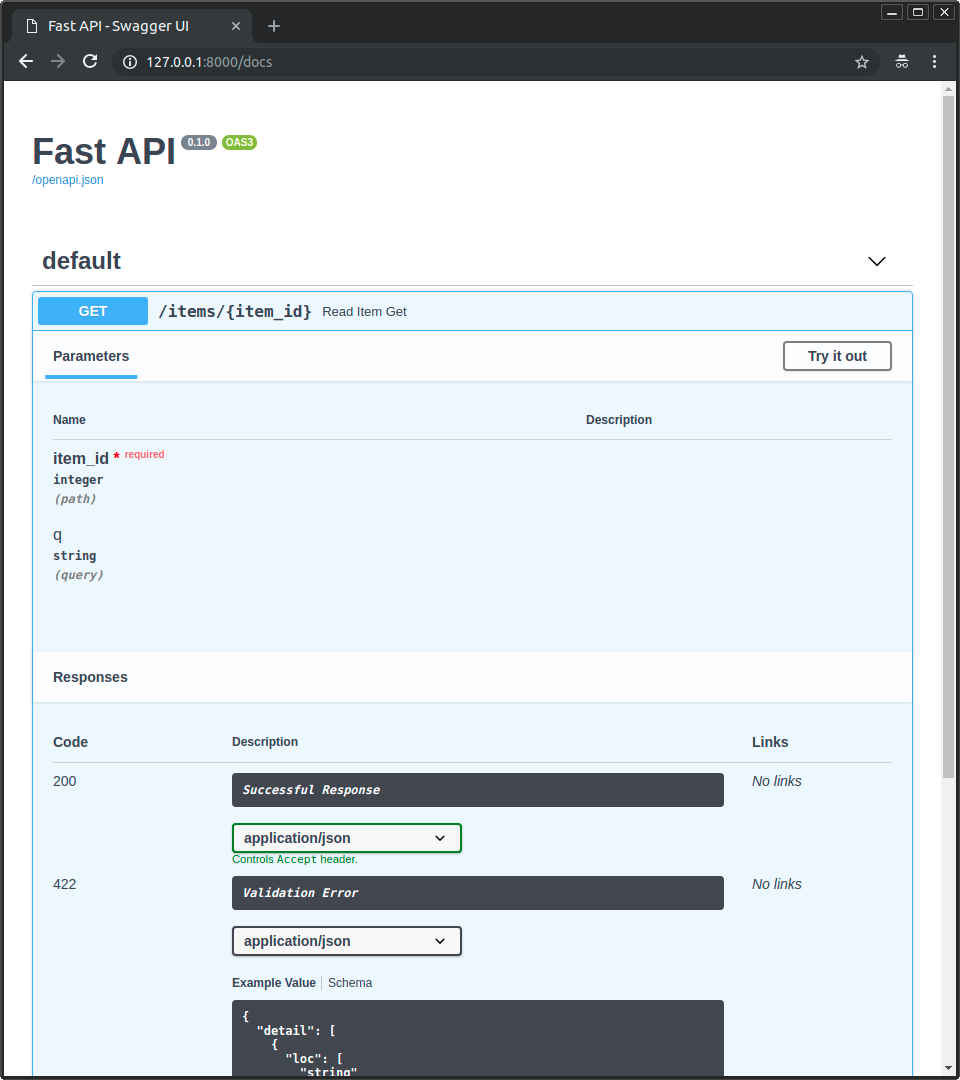

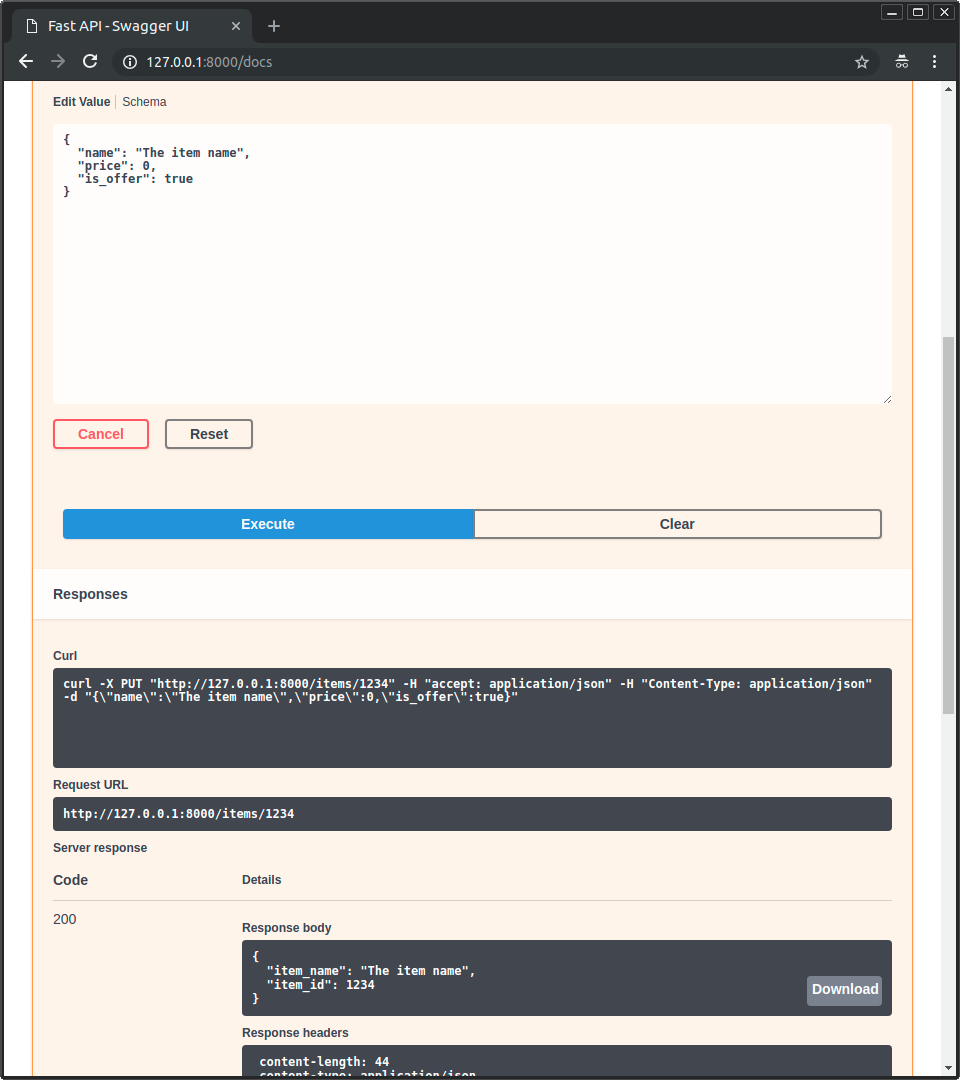

## Check the Docs |

|||

|

|||

You can see the defined cookies in the docs UI at `/docs`: |

|||

|

|||

<div class="screenshot"> |

|||

<img src="/img/tutorial/cookie-param-models/image01.png"> |

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

/// info |

|||

|

|||

Have in mind that, as **browsers handle cookies** in special ways and behind the scenes, they **don't** easily allow **JavaScript** to touch them. |

|||

|

|||

If you go to the **API docs UI** at `/docs` you will be able to see the **documentation** for cookies for your *path operations*. |

|||

|

|||

But even if you **fill the data** and click "Execute", because the docs UI works with **JavaScript**, the cookies won't be sent, and you will see an **error** message as if you didn't write any values. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

## Forbid Extra Cookies |

|||

|

|||

In some special use cases (probably not very common), you might want to **restrict** the cookies that you want to receive. |

|||

|

|||

Your API now has the power to control its own <abbr title="This is a joke, just in case. It has nothing to do with cookie consents, but it's funny that even the API can now reject the poor cookies. Have a cookie. 🍪">cookie consent</abbr>. 🤪🍪 |

|||

|

|||

You can use Pydantic's model configuration to `forbid` any `extra` fields: |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.9+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="10" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/cookie_param_models/tutorial002_an_py39.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.8+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="11" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/cookie_param_models/tutorial002_an.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.8+ non-Annotated |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Prefer to use the `Annotated` version if possible. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="10" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/cookie_param_models/tutorial002.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

If a client tries to send some **extra cookies**, they will receive an **error** response. |

|||

|

|||

Poor cookie banners with all their effort to get your consent for the <abbr title="This is another joke. Don't pay attention to me. Have some coffee for your cookie. ☕">API to reject it</abbr>. 🍪 |

|||

|

|||

For example, if the client tries to send a `santa_tracker` cookie with a value of `good-list-please`, the client will receive an **error** response telling them that the `santa_tracker` <abbr title="Santa disapproves the lack of cookies. 🎅 Okay, no more cookie jokes.">cookie is not allowed</abbr>: |

|||

|

|||

```json |

|||

{ |

|||

"detail": [ |

|||

{ |

|||

"type": "extra_forbidden", |

|||

"loc": ["cookie", "santa_tracker"], |

|||

"msg": "Extra inputs are not permitted", |

|||

"input": "good-list-please", |

|||

} |

|||

] |

|||

} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

## Summary |

|||

|

|||

You can use **Pydantic models** to declare <abbr title="Have a last cookie before you go. 🍪">**cookies**</abbr> in **FastAPI**. 😎 |

|||

@ -0,0 +1,184 @@ |

|||

# Header Parameter Models |

|||

|

|||

If you have a group of related **header parameters**, you can create a **Pydantic model** to declare them. |

|||

|

|||

This would allow you to **re-use the model** in **multiple places** and also to declare validations and metadata for all the parameters at once. 😎 |

|||

|

|||

/// note |

|||

|

|||

This is supported since FastAPI version `0.115.0`. 🤓 |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

## Header Parameters with a Pydantic Model |

|||

|

|||

Declare the **header parameters** that you need in a **Pydantic model**, and then declare the parameter as `Header`: |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.10+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="9-14 18" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/header_param_models/tutorial001_an_py310.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.9+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="9-14 18" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/header_param_models/tutorial001_an_py39.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.8+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="10-15 19" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/header_param_models/tutorial001_an.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.10+ non-Annotated |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Prefer to use the `Annotated` version if possible. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="7-12 16" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/header_param_models/tutorial001_py310.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.9+ non-Annotated |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Prefer to use the `Annotated` version if possible. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="9-14 18" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/header_param_models/tutorial001_py39.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.8+ non-Annotated |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Prefer to use the `Annotated` version if possible. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="7-12 16" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/header_param_models/tutorial001_py310.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

**FastAPI** will **extract** the data for **each field** from the **headers** in the request and give you the Pydantic model you defined. |

|||

|

|||

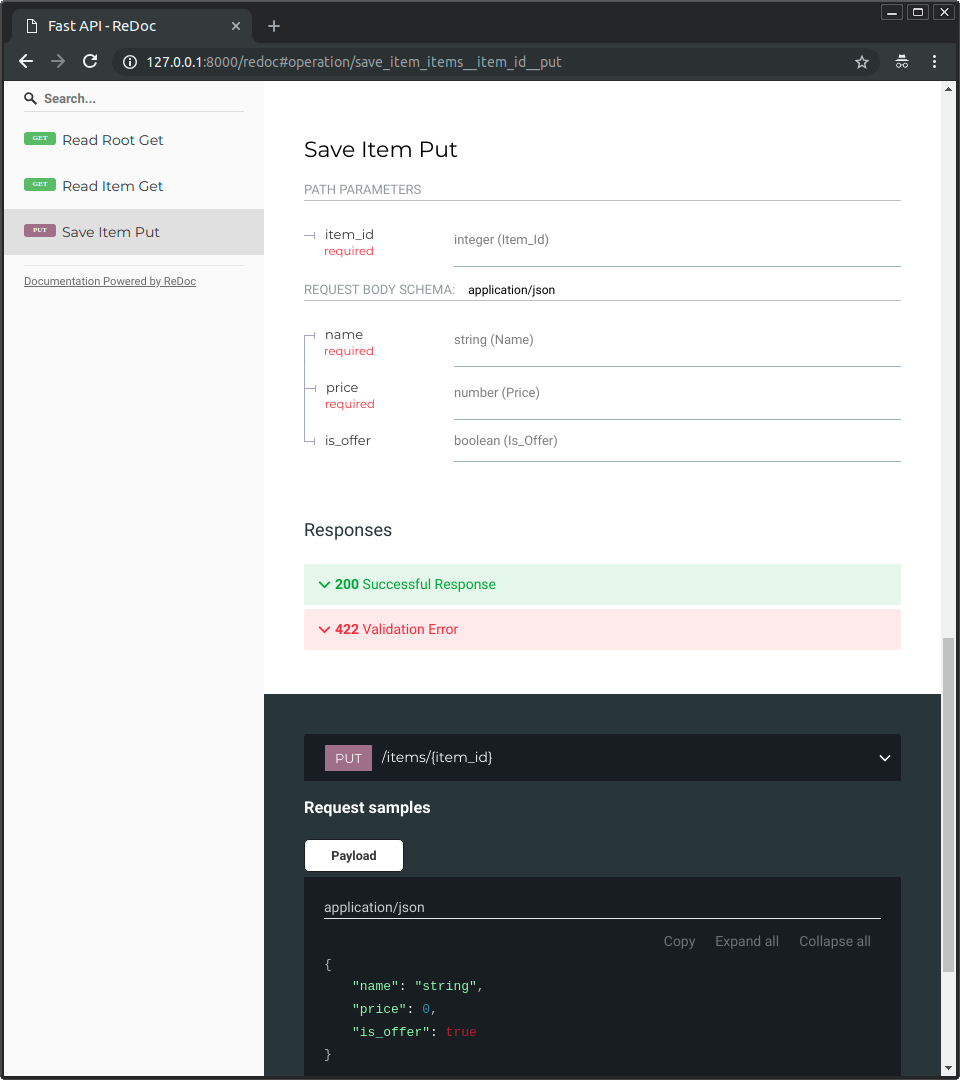

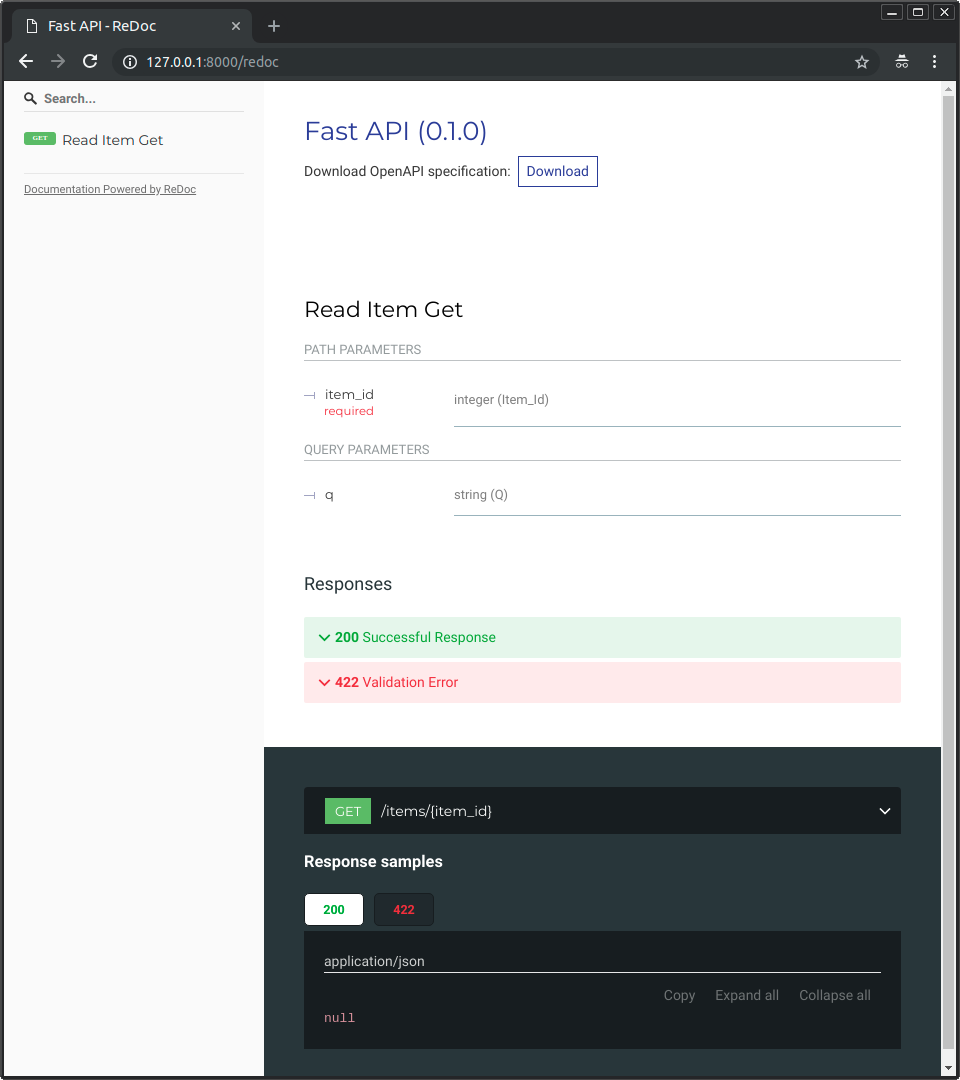

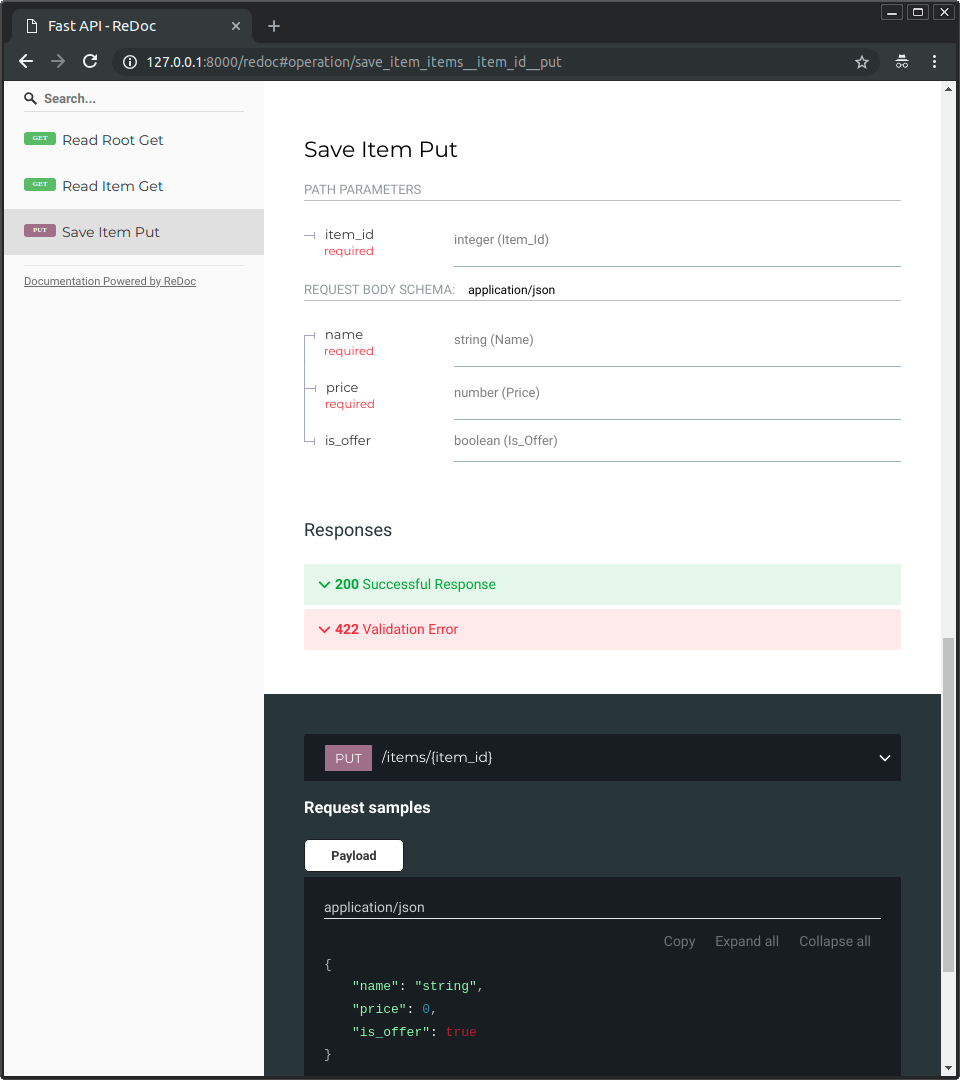

## Check the Docs |

|||

|

|||

You can see the required headers in the docs UI at `/docs`: |

|||

|

|||

<div class="screenshot"> |

|||

<img src="/img/tutorial/header-param-models/image01.png"> |

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

## Forbid Extra Headers |

|||

|

|||

In some special use cases (probably not very common), you might want to **restrict** the headers that you want to receive. |

|||

|

|||

You can use Pydantic's model configuration to `forbid` any `extra` fields: |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.10+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="10" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/header_param_models/tutorial002_an_py310.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.9+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="10" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/header_param_models/tutorial002_an_py39.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.8+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="11" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/header_param_models/tutorial002_an.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.10+ non-Annotated |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Prefer to use the `Annotated` version if possible. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="8" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/header_param_models/tutorial002_py310.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.9+ non-Annotated |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Prefer to use the `Annotated` version if possible. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="10" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/header_param_models/tutorial002_py39.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.8+ non-Annotated |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Prefer to use the `Annotated` version if possible. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="10" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/header_param_models/tutorial002.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

If a client tries to send some **extra headers**, they will receive an **error** response. |

|||

|

|||

For example, if the client tries to send a `tool` header with a value of `plumbus`, they will receive an **error** response telling them that the header parameter `tool` is not allowed: |

|||

|

|||

```json |

|||

{ |

|||

"detail": [ |

|||

{ |

|||

"type": "extra_forbidden", |

|||

"loc": ["header", "tool"], |

|||

"msg": "Extra inputs are not permitted", |

|||

"input": "plumbus", |

|||

} |

|||

] |

|||

} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

## Summary |

|||

|

|||

You can use **Pydantic models** to declare **headers** in **FastAPI**. 😎 |

|||

@ -0,0 +1,196 @@ |

|||

# Query Parameter Models |

|||

|

|||

If you have a group of **query parameters** that are related, you can create a **Pydantic model** to declare them. |

|||

|

|||

This would allow you to **re-use the model** in **multiple places** and also to declare validations and metadata for all the parameters at once. 😎 |

|||

|

|||

/// note |

|||

|

|||

This is supported since FastAPI version `0.115.0`. 🤓 |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

## Query Parameters with a Pydantic Model |

|||

|

|||

Declare the **query parameters** that you need in a **Pydantic model**, and then declare the parameter as `Query`: |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.10+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="9-13 17" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/query_param_models/tutorial001_an_py310.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.9+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="8-12 16" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/query_param_models/tutorial001_an_py39.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.8+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="10-14 18" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/query_param_models/tutorial001_an.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.10+ non-Annotated |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Prefer to use the `Annotated` version if possible. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="9-13 17" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/query_param_models/tutorial001_py310.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.9+ non-Annotated |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Prefer to use the `Annotated` version if possible. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="8-12 16" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/query_param_models/tutorial001_py39.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.8+ non-Annotated |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Prefer to use the `Annotated` version if possible. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="9-13 17" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/query_param_models/tutorial001_py310.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

**FastAPI** will **extract** the data for **each field** from the **query parameters** in the request and give you the Pydantic model you defined. |

|||

|

|||

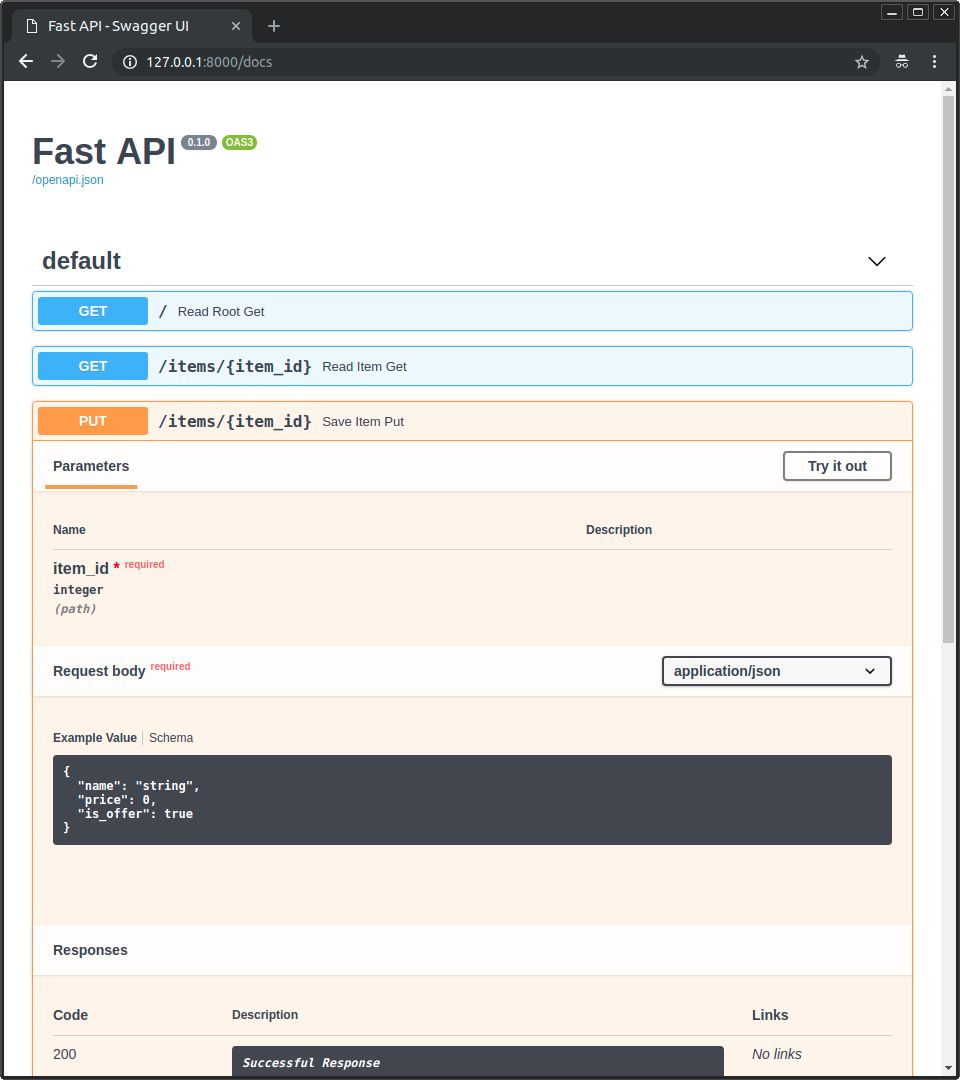

## Check the Docs |

|||

|

|||

You can see the query parameters in the docs UI at `/docs`: |

|||

|

|||

<div class="screenshot"> |

|||

<img src="/img/tutorial/query-param-models/image01.png"> |

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

## Forbid Extra Query Parameters |

|||

|

|||

In some special use cases (probably not very common), you might want to **restrict** the query parameters that you want to receive. |

|||

|

|||

You can use Pydantic's model configuration to `forbid` any `extra` fields: |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.10+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="10" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/query_param_models/tutorial002_an_py310.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.9+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="9" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/query_param_models/tutorial002_an_py39.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.8+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="11" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/query_param_models/tutorial002_an.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.10+ non-Annotated |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Prefer to use the `Annotated` version if possible. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="10" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/query_param_models/tutorial002_py310.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.9+ non-Annotated |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Prefer to use the `Annotated` version if possible. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="9" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/query_param_models/tutorial002_py39.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.8+ non-Annotated |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Prefer to use the `Annotated` version if possible. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="11" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/query_param_models/tutorial002.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

If a client tries to send some **extra** data in the **query parameters**, they will receive an **error** response. |

|||

|

|||

For example, if the client tries to send a `tool` query parameter with a value of `plumbus`, like: |

|||

|

|||

```http |

|||

https://example.com/items/?limit=10&tool=plumbus |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

They will receive an **error** response telling them that the query parameter `tool` is not allowed: |

|||

|

|||

```json |

|||

{ |

|||

"detail": [ |

|||

{ |

|||

"type": "extra_forbidden", |

|||

"loc": ["query", "tool"], |

|||

"msg": "Extra inputs are not permitted", |

|||

"input": "plumbus" |

|||

} |

|||

] |

|||

} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

## Summary |

|||

|

|||

You can use **Pydantic models** to declare **query parameters** in **FastAPI**. 😎 |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Spoiler alert: you can also use Pydantic models to declare cookies and headers, but you will read about that later in the tutorial. 🤫 |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

@ -0,0 +1,134 @@ |

|||

# Form Models |

|||

|

|||

You can use **Pydantic models** to declare **form fields** in FastAPI. |

|||

|

|||

/// info |

|||

|

|||

To use forms, first install <a href="https://github.com/Kludex/python-multipart" class="external-link" target="_blank">`python-multipart`</a>. |

|||

|

|||

Make sure you create a [virtual environment](../virtual-environments.md){.internal-link target=_blank}, activate it, and then install it, for example: |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ pip install python-multipart |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

/// note |

|||

|

|||

This is supported since FastAPI version `0.113.0`. 🤓 |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

## Pydantic Models for Forms |

|||

|

|||

You just need to declare a **Pydantic model** with the fields you want to receive as **form fields**, and then declare the parameter as `Form`: |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.9+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="9-11 15" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/request_form_models/tutorial001_an_py39.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.8+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="8-10 14" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/request_form_models/tutorial001_an.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.8+ non-Annotated |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Prefer to use the `Annotated` version if possible. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="7-9 13" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/request_form_models/tutorial001.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

**FastAPI** will **extract** the data for **each field** from the **form data** in the request and give you the Pydantic model you defined. |

|||

|

|||

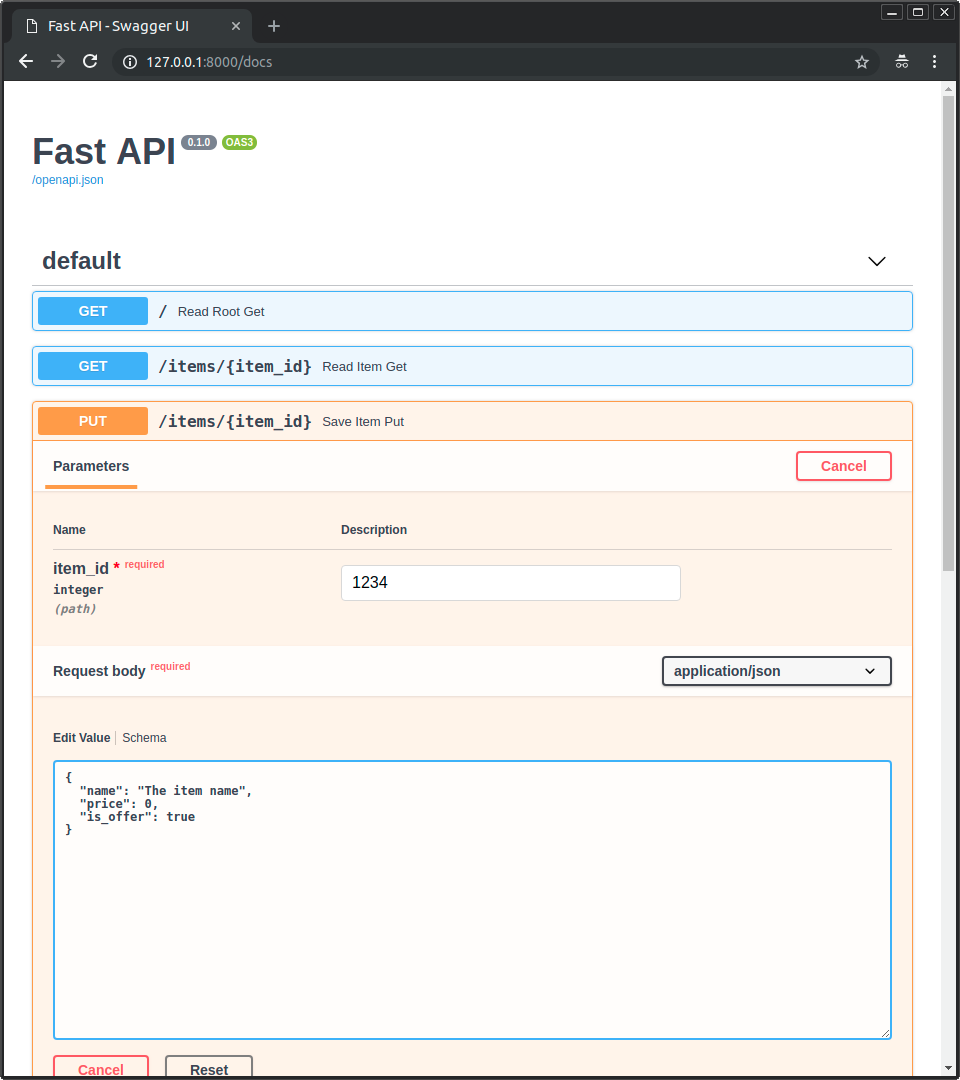

## Check the Docs |

|||

|

|||

You can verify it in the docs UI at `/docs`: |

|||

|

|||

<div class="screenshot"> |

|||

<img src="/img/tutorial/request-form-models/image01.png"> |

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

## Forbid Extra Form Fields |

|||

|

|||

In some special use cases (probably not very common), you might want to **restrict** the form fields to only those declared in the Pydantic model. And **forbid** any **extra** fields. |

|||

|

|||

/// note |

|||

|

|||

This is supported since FastAPI version `0.114.0`. 🤓 |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

You can use Pydantic's model configuration to `forbid` any `extra` fields: |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.9+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="12" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/request_form_models/tutorial002_an_py39.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.8+ |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="11" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/request_form_models/tutorial002_an.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Python 3.8+ non-Annotated |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Prefer to use the `Annotated` version if possible. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

```Python hl_lines="10" |

|||

{!> ../../../docs_src/request_form_models/tutorial002.py!} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

If a client tries to send some extra data, they will receive an **error** response. |

|||

|

|||

For example, if the client tries to send the form fields: |

|||

|

|||

* `username`: `Rick` |

|||

* `password`: `Portal Gun` |

|||

* `extra`: `Mr. Poopybutthole` |

|||

|

|||

They will receive an error response telling them that the field `extra` is not allowed: |

|||

|

|||

```json |

|||

{ |

|||

"detail": [ |

|||

{ |

|||

"type": "extra_forbidden", |

|||

"loc": ["body", "extra"], |

|||

"msg": "Extra inputs are not permitted", |

|||

"input": "Mr. Poopybutthole" |

|||

} |

|||

] |

|||

} |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

## Summary |

|||

|

|||

You can use Pydantic models to declare form fields in FastAPI. 😎 |

|||

@ -0,0 +1,844 @@ |

|||

# Virtual Environments |

|||

|

|||

When you work in Python projects you probably should use a **virtual environment** (or a similar mechanism) to isolate the packages you install for each project. |

|||

|

|||

/// info |

|||

|

|||

If you already know about virtual environments, how to create them and use them, you might want to skip this section. 🤓 |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

A **virtual environment** is different than an **environment variable**. |

|||

|

|||

An **environment variable** is a variable in the system that can be used by programs. |

|||

|

|||

A **virtual environment** is a directory with some files in it. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

/// info |

|||

|

|||

This page will teach you how to use **virtual environments** and how they work. |

|||

|

|||

If you are ready to adopt a **tool that manages everything** for you (including installing Python), try <a href="https://github.com/astral-sh/uv" class="external-link" target="_blank">uv</a>. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

## Create a Project |

|||

|

|||

First, create a directory for your project. |

|||

|

|||

What I normally do is that I create a directory named `code` inside my home/user directory. |

|||

|

|||

And inside of that I create one directory per project. |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

// Go to the home directory |

|||

$ cd |

|||

// Create a directory for all your code projects |

|||

$ mkdir code |

|||

// Enter into that code directory |

|||

$ cd code |

|||

// Create a directory for this project |

|||

$ mkdir awesome-project |

|||

// Enter into that project directory |

|||

$ cd awesome-project |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

## Create a Virtual Environment |

|||

|

|||

When you start working on a Python project **for the first time**, create a virtual environment **<abbr title="there are other options, this is a simple guideline">inside your project</abbr>**. |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

You only need to do this **once per project**, not every time you work. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | `venv` |

|||

|

|||

To create a virtual environment, you can use the `venv` module that comes with Python. |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ python -m venv .venv |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

/// details | What that command means |

|||

|

|||

* `python`: use the program called `python` |

|||

* `-m`: call a module as a script, we'll tell it which module next |

|||

* `venv`: use the module called `venv` that normally comes installed with Python |

|||

* `.venv`: create the virtual environment in the new directory `.venv` |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | `uv` |

|||

|

|||

If you have <a href="https://github.com/astral-sh/uv" class="external-link" target="_blank">`uv`</a> installed, you can use it to create a virtual environment. |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ uv venv |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

By default, `uv` will create a virtual environment in a directory called `.venv`. |

|||

|

|||

But you could customize it passing an additional argument with the directory name. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

That command creates a new virtual environment in a directory called `.venv`. |

|||

|

|||

/// details | `.venv` or other name |

|||

|

|||

You could create the virtual environment in a different directory, but there's a convention of calling it `.venv`. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

## Activate the Virtual Environment |

|||

|

|||

Activate the new virtual environment so that any Python command you run or package you install uses it. |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Do this **every time** you start a **new terminal session** to work on the project. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Linux, macOS |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ source .venv/bin/activate |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Windows PowerShell |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ .venv\Scripts\Activate.ps1 |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Windows Bash |

|||

|

|||

Or if you use Bash for Windows (e.g. <a href="https://gitforwindows.org/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Git Bash</a>): |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ source .venv/Scripts/activate |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Every time you install a **new package** in that environment, **activate** the environment again. |

|||

|

|||

This makes sure that if you use a **terminal (<abbr title="command line interface">CLI</abbr>) program** installed by that package, you use the one from your virtual environment and not any other that could be installed globally, probably with a different version than what you need. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

## Check the Virtual Environment is Active |

|||

|

|||

Check that the virtual environment is active (the previous command worked). |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

This is **optional**, but it's a good way to **check** that everything is working as expected and you are using the virtual environment you intended. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Linux, macOS, Windows Bash |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ which python |

|||

|

|||

/home/user/code/awesome-project/.venv/bin/python |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

If it shows the `python` binary at `.venv/bin/python`, inside of your project (in this case `awesome-project`), then it worked. 🎉 |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Windows PowerShell |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ Get-Command python |

|||

|

|||

C:\Users\user\code\awesome-project\.venv\Scripts\python |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

If it shows the `python` binary at `.venv\Scripts\python`, inside of your project (in this case `awesome-project`), then it worked. 🎉 |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

## Upgrade `pip` |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

If you use <a href="https://github.com/astral-sh/uv" class="external-link" target="_blank">`uv`</a> you would use it to install things instead of `pip`, so you don't need to upgrade `pip`. 😎 |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

If you are using `pip` to install packages (it comes by default with Python), you should **upgrade** it to the latest version. |

|||

|

|||

Many exotic errors while installing a package are solved by just upgrading `pip` first. |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

You would normally do this **once**, right after you create the virtual environment. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

Make sure the virtual environment is active (with the command above) and then run: |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ python -m pip install --upgrade pip |

|||

|

|||

---> 100% |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

## Add `.gitignore` |

|||

|

|||

If you are using **Git** (you should), add a `.gitignore` file to exclude everything in your `.venv` from Git. |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

If you used <a href="https://github.com/astral-sh/uv" class="external-link" target="_blank">`uv`</a> to create the virtual environment, it already did this for you, you can skip this step. 😎 |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Do this **once**, right after you create the virtual environment. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ echo "*" > .venv/.gitignore |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

/// details | What that command means |

|||

|

|||

* `echo "*"`: will "print" the text `*` in the terminal (the next part changes that a bit) |

|||

* `>`: anything printed to the terminal by the command to the left of `>` should not be printed but instead written to the file that goes to the right of `>` |

|||

* `.gitignore`: the name of the file where the text should be written |

|||

|

|||

And `*` for Git means "everything". So, it will ignore everything in the `.venv` directory. |

|||

|

|||

That command will create a file `.gitignore` with the content: |

|||

|

|||

```gitignore |

|||

* |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

## Install Packages |

|||

|

|||

After activating the environment, you can install packages in it. |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Do this **once** when installing or upgrading the packages your project needs. |

|||

|

|||

If you need to upgrade a version or add a new package you would **do this again**. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

### Install Packages Directly |

|||

|

|||

If you're in a hurry and don't want to use a file to declare your project's package requirements, you can install them directly. |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

It's a (very) good idea to put the packages and versions your program needs in a file (for example `requirements.txt` or `pyproject.toml`). |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | `pip` |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ pip install "fastapi[standard]" |

|||

|

|||

---> 100% |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | `uv` |

|||

|

|||

If you have <a href="https://github.com/astral-sh/uv" class="external-link" target="_blank">`uv`</a>: |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ uv pip install "fastapi[standard]" |

|||

---> 100% |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

### Install from `requirements.txt` |

|||

|

|||

If you have a `requirements.txt`, you can now use it to install its packages. |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | `pip` |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ pip install -r requirements.txt |

|||

---> 100% |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | `uv` |

|||

|

|||

If you have <a href="https://github.com/astral-sh/uv" class="external-link" target="_blank">`uv`</a>: |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ uv pip install -r requirements.txt |

|||

---> 100% |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

/// details | `requirements.txt` |

|||

|

|||

A `requirements.txt` with some packages could look like: |

|||

|

|||

```requirements.txt |

|||

fastapi[standard]==0.113.0 |

|||

pydantic==2.8.0 |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

## Run Your Program |

|||

|

|||

After you activated the virtual environment, you can run your program, and it will use the Python inside of your virtual environment with the packages you installed there. |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ python main.py |

|||

|

|||

Hello World |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

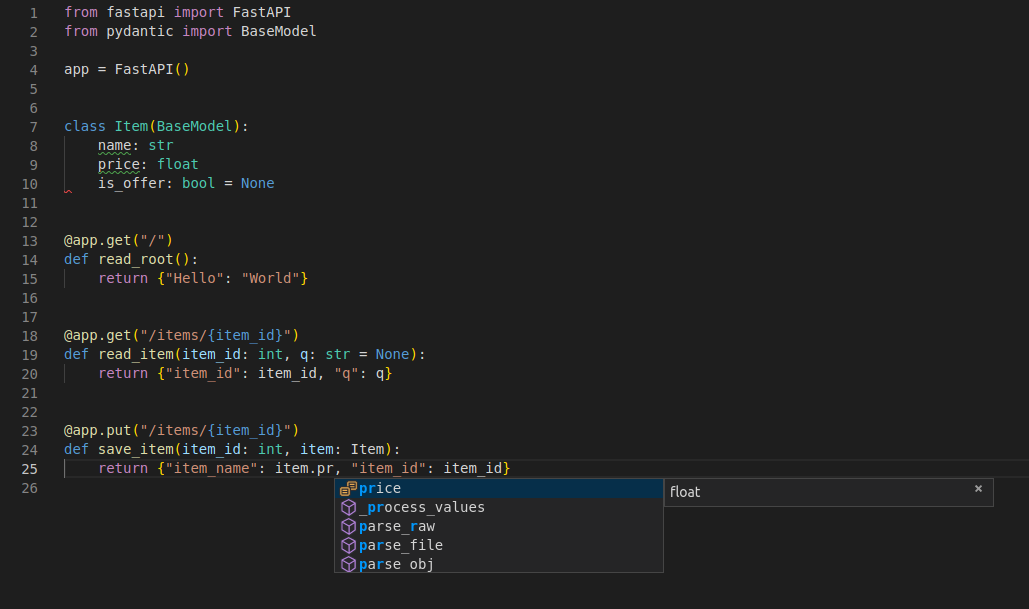

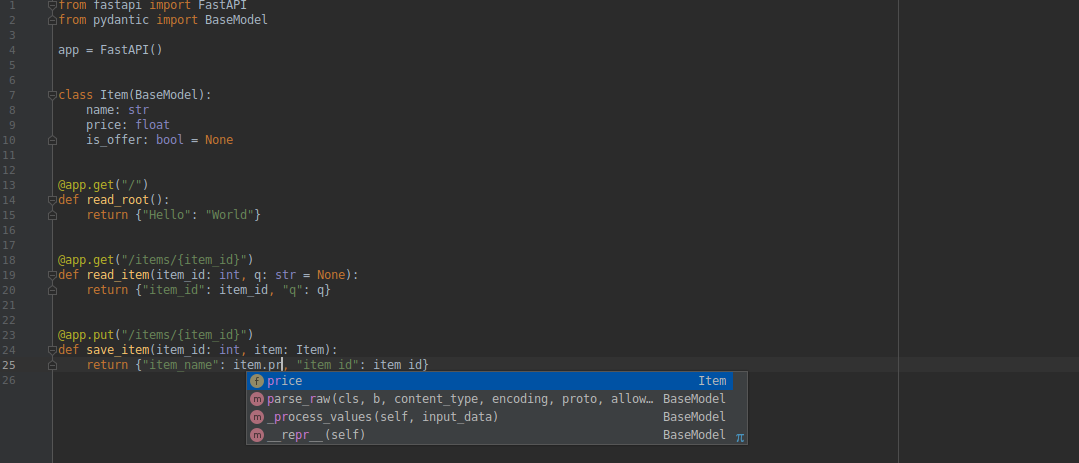

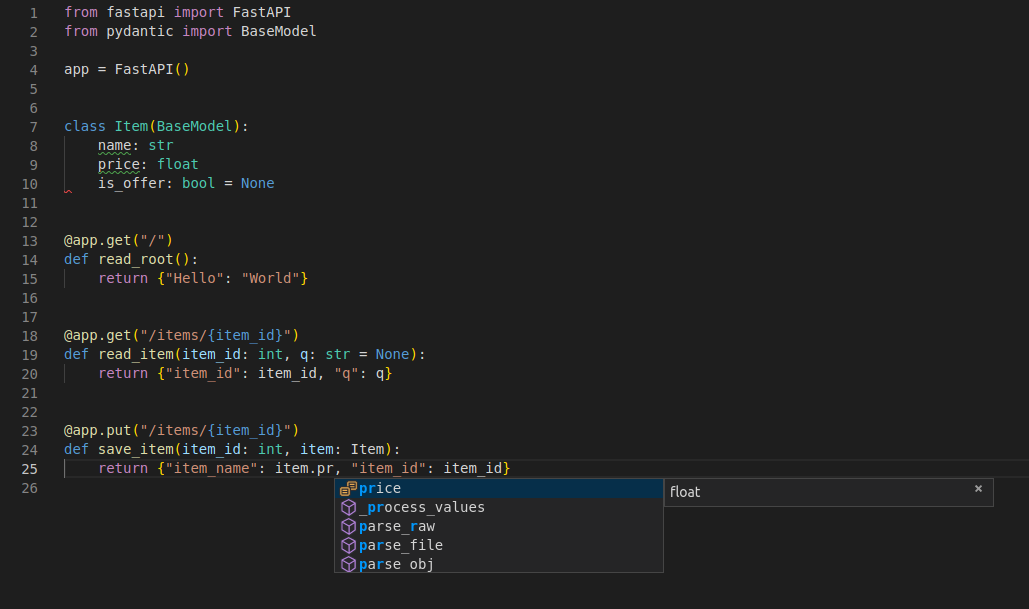

## Configure Your Editor |

|||

|

|||

You would probably use an editor, make sure you configure it to use the same virtual environment you created (it will probably autodetect it) so that you can get autocompletion and inline errors. |

|||

|

|||

For example: |

|||

|

|||

* <a href="https://code.visualstudio.com/docs/python/environments#_select-and-activate-an-environment" class="external-link" target="_blank">VS Code</a> |

|||

* <a href="https://www.jetbrains.com/help/pycharm/creating-virtual-environment.html" class="external-link" target="_blank">PyCharm</a> |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

You normally have to do this only **once**, when you create the virtual environment. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

## Deactivate the Virtual Environment |

|||

|

|||

Once you are done working on your project you can **deactivate** the virtual environment. |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ deactivate |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

This way, when you run `python` it won't try to run it from that virtual environment with the packages installed there. |

|||

|

|||

## Ready to Work |

|||

|

|||

Now you're ready to start working on your project. |

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

Do you want to understand what's all that above? |

|||

|

|||

Continue reading. 👇🤓 |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

## Why Virtual Environments |

|||

|

|||

To work with FastAPI you need to install <a href="https://www.python.org/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Python</a>. |

|||

|

|||

After that, you would need to **install** FastAPI and any other **packages** you want to use. |

|||

|

|||

To install packages you would normally use the `pip` command that comes with Python (or similar alternatives). |

|||

|

|||

Nevertheless, if you just use `pip` directly, the packages would be installed in your **global Python environment** (the global installation of Python). |

|||

|

|||

### The Problem |

|||

|

|||

So, what's the problem with installing packages in the global Python environment? |

|||

|

|||

At some point, you will probably end up writing many different programs that depend on **different packages**. And some of these projects you work on will depend on **different versions** of the same package. 😱 |

|||

|

|||

For example, you could create a project called `philosophers-stone`, this program depends on another package called **`harry`, using the version `1`**. So, you need to install `harry`. |

|||

|

|||

```mermaid |

|||

flowchart LR |

|||

stone(philosophers-stone) -->|requires| harry-1[harry v1] |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

Then, at some point later, you create another project called `prisoner-of-azkaban`, and this project also depends on `harry`, but this project needs **`harry` version `3`**. |

|||

|

|||

```mermaid |

|||

flowchart LR |

|||

azkaban(prisoner-of-azkaban) --> |requires| harry-3[harry v3] |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

But now the problem is, if you install the packages globally (in the global environment) instead of in a local **virtual environment**, you will have to choose which version of `harry` to install. |

|||

|

|||

If you want to run `philosophers-stone` you will need to first install `harry` version `1`, for example with: |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ pip install "harry==1" |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

And then you would end up with `harry` version `1` installed in your global Python environment. |

|||

|

|||

```mermaid |

|||

flowchart LR |

|||

subgraph global[global env] |

|||

harry-1[harry v1] |

|||

end |

|||

subgraph stone-project[philosophers-stone project] |

|||

stone(philosophers-stone) -->|requires| harry-1 |

|||

end |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

But then if you want to run `prisoner-of-azkaban`, you will need to uninstall `harry` version `1` and install `harry` version `3` (or just installing version `3` would automatically uninstall version `1`). |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ pip install "harry==3" |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

And then you would end up with `harry` version `3` installed in your global Python environment. |

|||

|

|||

And if you try to run `philosophers-stone` again, there's a chance it would **not work** because it needs `harry` version `1`. |

|||

|

|||

```mermaid |

|||

flowchart LR |

|||

subgraph global[global env] |

|||

harry-1[<strike>harry v1</strike>] |

|||

style harry-1 fill:#ccc,stroke-dasharray: 5 5 |

|||

harry-3[harry v3] |

|||

end |

|||

subgraph stone-project[philosophers-stone project] |

|||

stone(philosophers-stone) -.-x|⛔️| harry-1 |

|||

end |

|||

subgraph azkaban-project[prisoner-of-azkaban project] |

|||

azkaban(prisoner-of-azkaban) --> |requires| harry-3 |

|||

end |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

It's very common in Python packages to try the best to **avoid breaking changes** in **new versions**, but it's better to be safe, and install newer versions intentionally and when you can run the tests to check everything is working correctly. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

Now, imagine that with **many** other **packages** that all your **projects depend on**. That's very difficult to manage. And you would probably end up running some projects with some **incompatible versions** of the packages, and not knowing why something isn't working. |

|||

|

|||

Also, depending on your operating system (e.g. Linux, Windows, macOS), it could have come with Python already installed. And in that case it probably had some packages pre-installed with some specific versions **needed by your system**. If you install packages in the global Python environment, you could end up **breaking** some of the programs that came with your operating system. |

|||

|

|||

## Where are Packages Installed |

|||

|

|||

When you install Python, it creates some directories with some files in your computer. |

|||

|

|||

Some of these directories are the ones in charge of having all the packages you install. |

|||

|

|||

When you run: |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

// Don't run this now, it's just an example 🤓 |

|||

$ pip install "fastapi[standard]" |

|||

---> 100% |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

That will download a compressed file with the FastAPI code, normally from <a href="https://pypi.org/project/fastapi/" class="external-link" target="_blank">PyPI</a>. |

|||

|

|||

It will also **download** files for other packages that FastAPI depends on. |

|||

|

|||

Then it will **extract** all those files and put them in a directory in your computer. |

|||

|

|||

By default, it will put those files downloaded and extracted in the directory that comes with your Python installation, that's the **global environment**. |

|||

|

|||

## What are Virtual Environments |

|||

|

|||

The solution to the problems of having all the packages in the global environment is to use a **virtual environment for each project** you work on. |

|||

|

|||

A virtual environment is a **directory**, very similar to the global one, where you can install the packages for a project. |

|||

|

|||

This way, each project will have its own virtual environment (`.venv` directory) with its own packages. |

|||

|

|||

```mermaid |

|||

flowchart TB |

|||

subgraph stone-project[philosophers-stone project] |

|||

stone(philosophers-stone) --->|requires| harry-1 |

|||

subgraph venv1[.venv] |

|||

harry-1[harry v1] |

|||

end |

|||

end |

|||

subgraph azkaban-project[prisoner-of-azkaban project] |

|||

azkaban(prisoner-of-azkaban) --->|requires| harry-3 |

|||

subgraph venv2[.venv] |

|||

harry-3[harry v3] |

|||

end |

|||

end |

|||

stone-project ~~~ azkaban-project |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

## What Does Activating a Virtual Environment Mean |

|||

|

|||

When you activate a virtual environment, for example with: |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Linux, macOS |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ source .venv/bin/activate |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Windows PowerShell |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ .venv\Scripts\Activate.ps1 |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Windows Bash |

|||

|

|||

Or if you use Bash for Windows (e.g. <a href="https://gitforwindows.org/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Git Bash</a>): |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ source .venv/Scripts/activate |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

That command will create or modify some [environment variables](environment-variables.md){.internal-link target=_blank} that will be available for the next commands. |

|||

|

|||

One of those variables is the `PATH` variable. |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

You can learn more about the `PATH` environment variable in the [Environment Variables](environment-variables.md#path-environment-variable){.internal-link target=_blank} section. |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

Activating a virtual environment adds its path `.venv/bin` (on Linux and macOS) or `.venv\Scripts` (on Windows) to the `PATH` environment variable. |

|||

|

|||

Let's say that before activating the environment, the `PATH` variable looked like this: |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Linux, macOS |

|||

|

|||

```plaintext |

|||

/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/sbin |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

That means that the system would look for programs in: |

|||

|

|||

* `/usr/bin` |

|||

* `/bin` |

|||

* `/usr/sbin` |

|||

* `/sbin` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Windows |

|||

|

|||

```plaintext |

|||

C:\Windows\System32 |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

That means that the system would look for programs in: |

|||

|

|||

* `C:\Windows\System32` |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

After activating the virtual environment, the `PATH` variable would look something like this: |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Linux, macOS |

|||

|

|||

```plaintext |

|||

/home/user/code/awesome-project/.venv/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/sbin |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

That means that the system will now start looking first look for programs in: |

|||

|

|||

```plaintext |

|||

/home/user/code/awesome-project/.venv/bin |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

before looking in the other directories. |

|||

|

|||

So, when you type `python` in the terminal, the system will find the Python program in |

|||

|

|||

```plaintext |

|||

/home/user/code/awesome-project/.venv/bin/python |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

and use that one. |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Windows |

|||

|

|||

```plaintext |

|||

C:\Users\user\code\awesome-project\.venv\Scripts;C:\Windows\System32 |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

That means that the system will now start looking first look for programs in: |

|||

|

|||

```plaintext |

|||

C:\Users\user\code\awesome-project\.venv\Scripts |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

before looking in the other directories. |

|||

|

|||

So, when you type `python` in the terminal, the system will find the Python program in |

|||

|

|||

```plaintext |

|||

C:\Users\user\code\awesome-project\.venv\Scripts\python |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

and use that one. |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

An important detail is that it will put the virtual environment path at the **beginning** of the `PATH` variable. The system will find it **before** finding any other Python available. This way, when you run `python`, it will use the Python **from the virtual environment** instead of any other `python` (for example, a `python` from a global environment). |

|||

|

|||

Activating a virtual environment also changes a couple of other things, but this is one of the most important things it does. |

|||

|

|||

## Checking a Virtual Environment |

|||

|

|||

When you check if a virtual environment is active, for example with: |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Linux, macOS, Windows Bash |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ which python |

|||

|

|||

/home/user/code/awesome-project/.venv/bin/python |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

//// tab | Windows PowerShell |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ Get-Command python |

|||

|

|||

C:\Users\user\code\awesome-project\.venv\Scripts\python |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

//// |

|||

|

|||

That means that the `python` program that will be used is the one **in the virtual environment**. |

|||

|

|||

you use `which` in Linux and macOS and `Get-Command` in Windows PowerShell. |

|||

|

|||

The way that command works is that it will go and check in the `PATH` environment variable, going through **each path in order**, looking for the program called `python`. Once it finds it, it will **show you the path** to that program. |

|||

|

|||

The most important part is that when you call `python`, that is the exact "`python`" that will be executed. |

|||

|

|||

So, you can confirm if you are in the correct virtual environment. |

|||

|

|||

/// tip |

|||

|

|||

It's easy to activate one virtual environment, get one Python, and then **go to another project**. |

|||

|

|||

And the second project **wouldn't work** because you are using the **incorrect Python**, from a virtual environment for another project. |

|||

|

|||

It's useful being able to check what `python` is being used. 🤓 |

|||

|

|||

/// |

|||

|

|||

## Why Deactivate a Virtual Environment |

|||

|

|||

For example, you could be working on a project `philosophers-stone`, **activate that virtual environment**, install packages and work with that environment. |

|||

|

|||

And then you want to work on **another project** `prisoner-of-azkaban`. |

|||

|

|||

You go to that project: |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ cd ~/code/prisoner-of-azkaban |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

If you don't deactivate the virtual environment for `philosophers-stone`, when you run `python` in the terminal, it will try to use the Python from `philosophers-stone`. |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ cd ~/code/prisoner-of-azkaban |

|||

|

|||

$ python main.py |

|||

|

|||

// Error importing sirius, it's not installed 😱 |

|||

Traceback (most recent call last): |

|||

File "main.py", line 1, in <module> |

|||

import sirius |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

But if you deactivate the virtual environment and activate the new one for `prisoner-of-askaban` then when you run `python` it will use the Python from the virtual environment in `prisoner-of-azkaban`. |

|||

|

|||

<div class="termy"> |

|||

|

|||

```console |

|||

$ cd ~/code/prisoner-of-azkaban |

|||

|

|||

// You don't need to be in the old directory to deactivate, you can do it wherever you are, even after going to the other project 😎 |

|||

$ deactivate |

|||

|

|||

// Activate the virtual environment in prisoner-of-azkaban/.venv 🚀 |

|||

$ source .venv/bin/activate |

|||

|

|||

// Now when you run python, it will find the package sirius installed in this virtual environment ✨ |

|||

$ python main.py |

|||

|

|||

I solemnly swear 🐺 |

|||

``` |

|||

|

|||

</div> |

|||

|

|||

## Alternatives |

|||

|

|||